The Alliance Report (TAR) is a leading global financial and business services magazine. For over two decades we have been helping people with all types of credit obtain the loan they need. We have spent time analyzing the lending marketplace...

SANDERS AGC

A GLOBAL MEDIA & ENTERTAINMENT COMPANY

Streamapse Media

Publishes News & Entertainment Offered Through Digital Online Magazines And News Websites and more.

Streamapse Media Podcast Network

A Podcast Production Company & Podcast Marketing Agency featuring top variety of editorial brands from around the web.

Allin Gaming & Entertainment

A group of Online Casinos for innovative Online Entertainment and Gaming such as House Of Games Casino, Brass Ring Casino, Coin Toss Poker Casino, and Babylon Games Casino.

What People Say

Sanders AGC will rigorously handle capital allocation and work to make sure each business is executing well.

Latest News

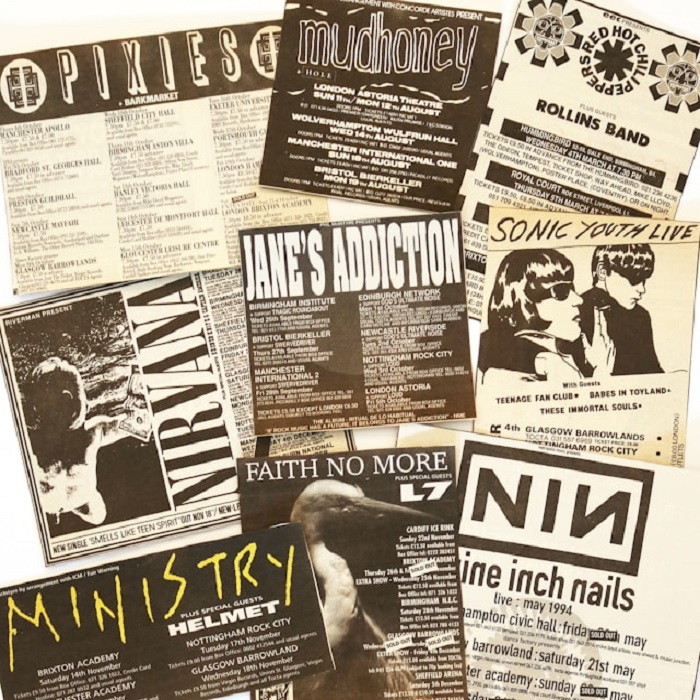

Part of the Streamapse Media Family. Your curated guide to the best live experiences, concerts, musical events, festivals, comedy events, sporting events news and more. Powered in part by TicketStream Networks Visit EncoreTSN

AllCoin CEX New Project Listings Top Cryptocurrencies & Recent Listings: Over the past few months, AllCoin CEX TOP performers include XMR, SOL,TON, KAS, LTC, and XRP. AllCoin CEX have listed over 15 new projects, incl. gems like Aethir (ETH), Synternet...